The Most Hated Woman In America

Her sons are beaten up regularly, abusive mail and phone calls pour in, bricks are thrown through her windows—yet nothing seems to faze the country’s No. 1 atheist, Madalyn Murray

Day after day the letters pour into the little office at 4547 Hanford Road, on the outskirts of Baltimore. Usually they are short and ugly: “You should be shot!” “Why don’t you go peddle your slop in Russia,” “YOU WICKID ANAMAL” “I will KILL you!” “You will go to Hell and burn burn burn forever.” “I pitty you in your ignorince.” “You believe in atheist which means you are a dirty Communist.” The day before Christmas a rock was thrown through the window, causing $67 worth of damage. Although the phone number is unlisted and is deliberately changed from time to time, through some black magic the vigilantes always learn the new number and call day and night with a barrage of insult, obscenity, threat, and psychotic rambling.

This is the office of Mrs. Madalyn Murray, the woman who fought—and won—the legal battle that resulted in the Supreme Court’s ban on prayer readings in public schools. She is surely the most hated woman in America. Recently an ordinary day’s mail brought the following:

A warning that God was going to strike her dead.

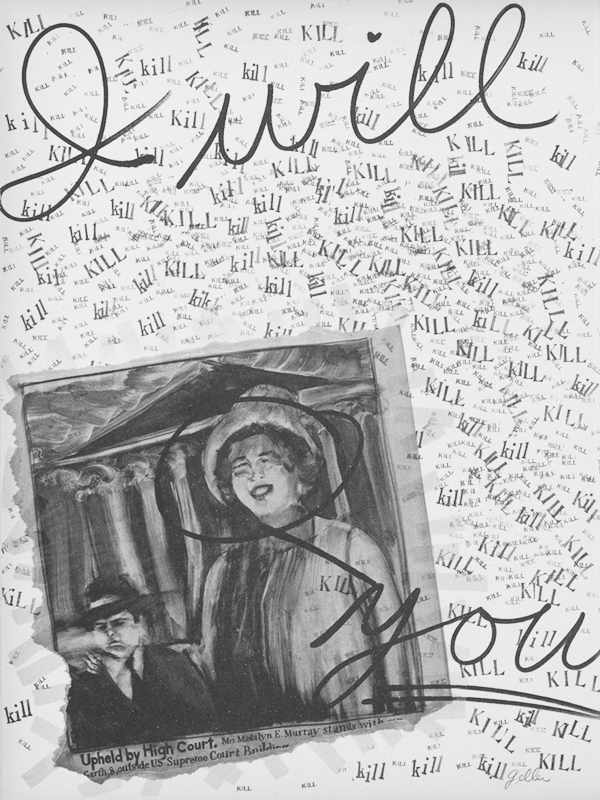

A psychotic-looking document, 22 inches by 30 inches, which began with “I will” and ended with “you,” and in between had the word “kill” repeated in various sizes several hundred times, with underlinings and exclamation points thrown in for further emphasis.

A photograph of herself, cut out of a local newspaper and smeared over with excrement.

Besides continuous harassment by mail and phone, Mrs. Murray has had to endure seeing her oldest son Bill, now 17, return from school beaten up by gangs of Catholic adolescents more than 100 times in the past three years. This persecution is now shifting to her younger son Garth, who is 9 and beginning to have night-mares because of frequent assaults by older boys.

When I first met Madalyn Murray, she seemed like any other Baltimore housewife—43 and graying, plump and plain. I expected her to prepare pies for church suppers, brush her teeth twice a day, and hide under the bed if Fidel Castro’s name were mentioned. Turkey-for-Thanksgiving, Bon-Amt on the shelf above the bathtub, “Put on your rubbers, dear, it’s snowing,” and other memories of my mother came back to mind as Hooked at her. This impression was smashed as soon as she opened her mouth, but the fact remains that, while she has read a few books and gotten herself some newfangled ideas, essentially Madalyn is a very uncomplicated person.

Contemplating the reactions to what she has done, Mrs. Murray is surprisingly calm. “In my own way,” she says, “I’m serving a necessary social function. This country has thousands of people crusading for the civil rights of un-believers, but none make themselves as obnoxious as I do. I figured, a few years ago, we have too many crusaders who arc moderate and temperate and careful and very, very status-conscious. I decided to be the kind of crusader who sticks her neck out and makes herself thoroughly unpopular.“

If this is her ambition, Madalyn Murray has undoubtedly succeeded. There arc 70 million people in America who belong to no church, and nobody knows for sure how many of them are actually atheists and how many are just “indifferent,” but no unbeliever has kicked up as much fury as Madalyn since the wild days of Clarence Darrow. Indeed, a measure of her achievement is the abuse presently being endured by her fellow Baltimorean, the Rev. Irving Murray of the First Unitarian Church. Not related to Madalyn in any way, not associated with any of her activities, Mr. Murray—because his name is the same as hers, and perhaps because his Unitarianism lends weight to Fundamentalists‘ suspicions—has been so disturbed by phone calls threatening “you and your Communist wife” that he, too, now has an unlisted number. It is certainly an indication that one has arrived as the nation’s No. 1 villain when those who only bear the same name share your unpopularity.

Madalyn’s stoical acceptance of unpopularity helps account for her outspokenness, which is nothing short of hair-raising. I asked her about the report, circulated verbally by a rival atheist organization, that she was secretly taking financial contributions from certain Southern racists. “I wish I could get some of their damned money,” she replied hotly. “You bet your life I’d take it.” I murmured something about there being various liberal and radical groups that would consider such money tainted. “Masochists,” she snapped. “I know that type. They like to be losers. Well, Madalyn Murray isn’t a loser. I never have been and I never will be. Anybody who doesn’t like it can kiss my ass.“

Even when she first blazed to national prominence in her celebrated fight to end Bible-and-prayer-reading in public schools, hers was not the temperate demeanor that unbelievers usually adopt in legal squabbles. In her first rumble with the Baltimore Board of Education, she told them, “I believe that the Virgin Mary probably played around as much as I did and certainly was capable of an orgasm.” She maintained this bluntness throughout the two years in which the case climbed from court to court. Nobody could escape learning that her contempt for the church is undisguised, unfrightened, and unlimited. She ruffled the feathers of that tough old rooster, Organized Religion, until he squawked and flapped his wings, and this is unique because the rooster has traditionally been first in the American pecking order. Everybody knows that the press can peck government, and government can peck industry, and industry can peck labor, and labor can peck all three of them back. But nobody can peck the rooster and the rooster can always peck anyone else, at any time, with impunity. All this has changed. Madalyn Murray went up to the Supreme Court in June, 1963, and pecked the living hell out of him. Worse: she is now beginning a new campaign that may peck him until he bleeds. And he would bleed that substance dearer even than blood in America: money.

![]()

On October 16 of last year, in Circuit Court 2 of Baltimore, Madalyn Murray filed suit to tax the church. She presented her case as a tax-payer and home-owner whose taxes are inordinately high because church property is not proportionately taxed. She intends to fight this case right up to the U.S. Supreme Court, as she fought the school-prayer case of 1961-63. This fight is going to be much nastier, though. All that the rooster lost in the school-prayer case was pride. This time he may lose his shirt.

On Nov. 4, 1963, only two weeks after Madalyn Murray filed her suit, the Catholic archdiocese of Baltimore entered the case. Madalyn, suit names only the tax officials of Baltimore as defendants, but the church is well aware of who the real defendants are. In Baltimore alone, according to the Baltimore News-Post of Nov. 4, 1963, the Catholic Church stands to lose millions of dollars if Mrs. Murray wins her case. How much will be lost by all the churches of the country it is impossible to calculate, but it will undoubtedly be the kind of figure that one usually sees attached to astronomical distances and national debts. The Catholic Church understands with .Id clarity what is at stake here. “The power to tax is the power to destroy,” said the Rt. Rev. George Hopkins, chancellor of the archdiocese of Baltimore, to a Baltimore American reporter on Nov. 3, 1963. “The power to tax is the power to destroy,” repeated Francis X. Gallagher, legal counsel for the archdiocese, to a reporter from the News-Post on November 4. “The power to tax is the power to destroy,” said a taxi driver to me when I was in Baltimore doing research for this article in January, 1964.

The fate of Madalyn’s tax-the-churches suit will probably not be settled for a few years, but most lawyers expect her to win. This, if it happens, will be the greatest blow organized religion has ever suffered in this nation. The economic pinch might well reduce the churches from their present towering pugnacity to the situation they occupy in such secularized nations as France or Mexico. Their strength will still be great, but it will not, any longer, be great enough to browbeat non-church members.

Of course, the reaction to this might start a process that will end with the churches stronger than ever. This can only happen, how-ever, if Fundamentalists, Catholics, and other interested groups can conquer their differences and unite to create a force capable of overruling the Supreme Court. The amendments now circulating through the state legislatures of the South, aimed at crippling the national government, may lay the groundwork for such an insurrection. In one way or another, Madalyn Murray is going to change the relationship of Church and State in some inordinate manner that we cannot guess in advance. The rooster may end up with a wrung neck or he may stand crowing over Madalyn’s defeated body, but he will certainly know that he has been in a fight. The pecking order will never be quite the same again.

Madalyn has planned her campaign carefully. She is president of Other Americans, an organization devoted to fighting for the civil liberties of those who do not believe in God or in the Christian religion. (The name is deliberately modeled upon that of another group, Protestants and Other Americans United for Separation of Church and State. “They just have the Protestants in their organization,” Madalyn says. “I’ve really got the Other Americans.“) Through Other Americans, she is helping to prepare nine other taxpayers suits in nine other states. Each will be filed by another atheist who is also a property-owner, and each will charge that the tax exemption on church property unfairly raises his own tax. The strategy of having ten cases is that this almost forces the U.S. Supreme Court to rule on the issue, for in ten state Supreme Courts there must be some disagreement, and when two state Supreme Courts disagree the U.S. Supreme Court must rule.

![]()

As if planning this historic fight did not keep Madalyn busy enough, she also edits a monthly magazine, the American Atheist, and runs a books-through-the-mail service. (Her best-selling titles are Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason. Homer Smith’s Man and His Gods, and a fat volume titled The Worlds Sixteen Crucified Saviors, or Christianity Before Christ, which purports to show that every single feature of the Christian religion was copied from earlier Oriental religions.) Other skirmishes occasionally draw Madalyn’s attention, too. When William Moore, the postman, was shot to death in Alabama last year on his trek across the South wearing an anti-segregation sign, the Negro churches of Baltimore united to give him a funeral. It was to be a Christian funeral, and in their press releases the Negro clergy continually referred to William Moore as a “perfect Christian.” Unfortunately, nobody had bothered to check on Mr. Moore’s actual beliefs, and the whole community was shocked when Madalyn announced that he was an atheist and had actually worked for her Other Americans for several months. Typically, Madalyn announced further that if the clergy dared to give hint a Christian funeral she would attend and “yell all through it that he was an atheist.” Mr. Moore was given a secular service.

What is Madalyn Murray, ultimate objective? She answers immediately: “Social revolution. I don’t want to die before I have made a revolution in America.” She is somewhat vague about what her new regime would be like, but she is crystal-clear about what it won’t be like. It will be neither Capitalistic nor Communistic. “The authoritarian Capitalist and the authoritarian bureaucrat both must go. Like Jefferson, we must oppose ‘every form of tyranny over the mind of man.’” She envisions a loose syndicate, or confederation, of workers‘ co-operatives owning the property of the country, and no State or Church having power above them. “Power and property both must be decentralized, and people must be taught to think for themselves, before the word ‘freedom’ will be more than a joke.” Madalyn grins suddenly. “This is my real dream,” she confess. “I get so sick and tired being called Madalyn-Murray-the-atheist, as if that’s all I am. Organized religion is only one of the power-monopolies that I aim to shake up before I let myself be buried.”

![]()

Madalyn Murray was born 43 years ago in Philadelphia, the daughter of a wealthy contractor. The first nine years of her life were happy and secure as only the first nine years of a white, upper-class Protestant can be happy and secure. She still remembers with pleasure the delight of knowing, as a small child, that many of the most beautiful buildings and public works in Philadelphia had been erected by her father. Then 1929 came, and for the next 11 years the world was like a series of blows to the head. Real poverty came finally, after years of sliding, and after real poverty were more years of insecurity while the whole nation struggled to climb out of the Depression. By 1940 the war boom had really begun and Madalyn’s family knew security again. But her adolescence had been the special hell that poverty brings to those of its victims who have known better times. She became a Socialist.

The Communist Party never attracted her, contrary to the opinion of her enemies. Madalyn was too individualistic to submit to any authoritarian organization, even if it did claim to be working for Socialism. Actually, her back-ground was so free of Red taint that, when she enlisted in the WACs in 1942, she was quickly cleared for highly classified code work and eventually joined Eisenhower’s personal staff in Europe.

During the war years Madalyn became increasingly disillusioned. She met Army brass and up close they seemed superficial. Through the U.S.O. she mingled with top stars of show business and decided they were “sexual pigs.” Politicians disillusioned her, too; their postwar refurbishing of Germany as “America’s ally” completed her cynicism.

As a psychiatric social worker she held positions with various governmental and private agencies and very quickly left—or was thrown out—when she began to argue that they were treating symptoms and refusing to face the major underlying problems. She drifted through the Socialist Workers‘ Party, the Socialist Party, the Socialist Labor Party, and the Progressive Party, finding them all “too hidebound and timid about basic issues.”

Finally, she began to discover the two ideas that really made sense to her. They were anarchism and atheism. The problems of poverty, racial injustice, political corruption, and everything else that we describe as “man’s inhumanity to man,” she began to argue, are all branches of a single evil tree, and that tree is Authority. Church and State are just two nets in which scoundrels trap fools. Obedience to Authority is the one single principle that explains every evil in human history. To think for oneself is, in her philosophy, not just a right and a privilege, but the highest duty of all. Any submission to Authority in which one does not completely believe becomes not just self-betrayal but the betrayal of all humanity. Her chief quarrel with supernatural religion is not just that she finds its claims unbelievable, but that it teaches men to distrust themselves and to submit to the orders and judgment of others. George Orwell’s tough aphorism “Freedom is the right to say No” became Madalyn Murray, personal credo. Her problems as a psychiatric social worker began to multiply. Instead of adjusting her clients to our society, she tried to teach them how to adjust society.

![]()

In 1961 her first truly s major battle began. Her oldest son, Bill, was then 14 and his upbringing had been thoroughly atheistic and anarchistic. “When Bill was 10,” Madalyn wrote later, “I expected him to read and understand Hiroshima and The Voyage of the Lucky Dragon. Our household gods were Clarence and Ruby Darrow, Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, Eugene V. Debs, Castellio, and Tom Paine. When he was 6 I started him on chess; I told him that he either beat me at the game when he was 8 or he could look for a new home. He can beat me at chess.” At 14, Bill announced that next semester he was not going to go through “that hogwash” of Bible reading and prayer recitation each morning at school. “I looked up at him, one inch taller than I was, and I said, well, if he was ready to take on our entire culture as an opponent, he could jolly well begin where he wanted to begin.”

Madalyn took Bill out of school. When the Board of Education threatened to prosecute, she brought him back and started her court fight. During the next three years she lost every single prelim, including the one in the State Supreme Court. Over in Pennsylvania, however, the State Supreme Court had upheld a group of Unitarians who were fighting on Madalyn, side, and the issue went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In June, 1963, Madalyn reached the main event and finally tasted victory.

Between 1961 and 1963 her son Bill was continually beaten up by gangs of ten or more adolescents. What is it like to enter physical combat a hundred times in a situation in which you cannot possibly win? I tried to draw Bill out about this.

“They never came alone,” Bill said broodingly. “Not once in all that time did any of them come for me alone. It was always a mob. Do you know why?”

I guessed that, since they were on God’s side, they could not afford to lose, lest God be disgraced.

“No,” he said. “They were afraid. Nobody has ever beaten me in a square fight.”

Madalyn’s mother is a Lutheran who never attends church. She gave up quarreling with Madalyn a long time ago, and, without any visible sign of distress, allows Madalyn to express her opinions and to live in her home. Once while I was talking to Madalyn her mother interrupted to say something to the effect, “Oh, Madalyn, you get worse every year, what a terrible thing to say,” but this was when Madalyn said she would not cast stones at people who were pro-miscuous, adulterous, homosexual, and so on. („People can do whatever they want sexually, as long as they don’t use force on anyone else” was approximately what Madalyn said.)

Madalyn has a brother living with her, and I didn’t even learn his name, so hostile was he to me. He hates Madalyn, hates her friends, hates reporters, hates everything that has made complications in his simple life. He works in a Baltimore factory. He never talks to anybody who comes to see Madalyn.

As for Madalyn’s divorced husband, he is a rather prominent man who does not wish to be known as having ever been associated with Madalyn.

Madalyn’s unpopularity with religious groups and with certain members of her family is understandable, but her unpopularity with irreligious groups mystified me. I left Baltimore to investigate it.

Roy Torcaso, president of the Washington, D.C., chapter of the American Humanist Association, is an avowed atheist. There is a distinct coolness between Madalyn Murray and the local branches of the American Humanist Association and I went to Mr. Torcaso’s home in Wheaton, Maryland, to ask him about it.

I found him to be a small, dark, dynamic man with the kind of eyes that are usually described as “piercing.” He spoke not in sentences but in paragraphs, and very carefully structured paragraphs, as logical and emotionless as a geometry book. He was quite willing to tell me anything I wanted to know about atheism, about humanism, about the differences between atheism and humanism, and about his own legal brawls with the Rooster, but he would not talk about Madalyn Murray for publication.

I tried another tack and read him a description of atheists written by a friend of mine. “The ones I’ve seen,” my friend wrote, “are mostly ugly, or crippled, or obviously maladjusted, and they have a grudge against the universe.”

Roy Tomaso listened thoughtfully, pondered a moment, and said, “That is obviously true about a certain percentage of the atheists I’ve known. I would say that this percentage might be approximately 15 or 20 per cent.”

It occurred to me that an opponent trying to bait Mr. Torcaso in a discussion would find the task rather fruitless. I switched the conversation back to Madalyn Murray and got a great many “No comments.”

I did manage to get some comments on Madalyn from other rationalist leaders. “She has no tact,” “She’s intemperate,” “She’s rash,” said three of them, who did, however, show a certain respect for her by asking not to be quoted directly.

Madalyn also has critics among liberals-at-large. A prominent Washington politician, who refused to be named, told me he had nightmares about her tax-the-churches suit. “Mrs. Murray has got to win,” he said. “Legally, the tax exemption for churches has never had a leg to stand on. It’s completely incompatible with the theory of democracy.

“But,” and he went almost completely pale as he said this, “can you imagine what will happen when the decision comes down? A Gallup poll shows most Americans still want prayer in the public schools, and an organization, been formed to overrule the Supreme Court, decision by a new Constitutional amendment. The upshot may be that the United States will wind up a theocratic state, just like Spain.”

![]()

Nothing, however, seems to faze the unsinkable Madalyn Murray. When I next saw her I told her what her fellow unbelievers were saying off the record, and she went on the record with: “They’re cowards. It’s not that they’re dishonest, basically. And they are very intelligent. They’re just frightened. They all hate my guts because whenever I open my mouth I say something akin to the horrible truth.“

She once wrote to a former executive director of the American Humanist Association, “You are yellow to the bone.” To my query about printing that, she shouted: “Sure, print it! Add that the whole organization is yellow to the bone. All these people who call themselves ‘humanists’ or ‘secularists’ or ‘agnostics’ or ‘free-thinkers’ are really atheists but they’re too cowardly to admit it.” I was suddenly reminded of what a high official of the American Civil Liberties Union told me: “According to Aristotle, courage is to know what to fear and what not to fear. Madalyn lacks that knowledge.” To Madalyn most people probably do seem a trifle cowardly. Even her enemies acknowledge her utter fearlessness.

Phone calls and mail continue to harass her. After Kennedy’s assassination, somebody wrote to Madalyn, “This was caused by spreaders of hatred like yourself.” Madalyn wrote back, “Why didn’t your God spare Kennedy? Why didn’t your prayers save him after the bullet was in him? And, lady, why don’t you see a psychiatrist?” About a month ago someone tried to break into her office at night. Her son Garth is still beaten up regularly. Sitting in her office interviewing her I heard a school bus go by. Every child stuck his head out the window and shouted. “Commie, Commie, Commie!”

The climate in Baltimore is particularly ugly. Baltimore is not the pastel-and-white mecca it seems when you pass through it quickly on a bus. It is a dirty, slummy, industrial town, almost as bad as Passaic, New Jersey, or the worst pans of New York or Chicago. In these mean streets live people who have been robbed of all that man has achieved in the last 6000 years, culturally and technologically. Civilization is owned and treasured and abused by their masters; these people only inhabit their city in the way that the mice do. They will form a mob and kill a person in two minutes if the right demogogue comes along to arouse them. Down these streets Madalyn Murray must walk each day. I will not be surprised if I read sometime that she has died by violence.

I spoke to a cab driver about Madalyn. “They should shoot that bitch,” he said congestedly, “or send her back to Communist China.” In fact, the thought of her sent him off on a diatribe against Earl Warren, Khrushchev, and several other devil-figures in his personal pantheon. He rambled on especially about five Negroes accused of raping a white woman in northern Maryland. He had emphatic ideas about what should be done with these Negroes, and told me of it in detail; it was all rather reminiscent of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom. “Just don’t waste a trial on animals like then, he kept repeating.

I asked him what church he attended.

“Saint Alphonse,” he replied at once.

“Do you attend mass every week?” I asked further.

“Never miss.”

As quietly as I could, I asked, “Did you ever hear any of the priests at Saint Alphonse speak against shooting people with unusual opinions or punishing them without a trial?”

“Oh hell, Jack,” he said, “a priest is in the public eye. They gotta say things like that.”

I told this to Madalyn and she laughed heartily. “You know,” she said, “somebody should really do a statistical study on how much morality is actually connected with church attendance. Who makes up the lynch mobs, atheists or Christians? Who commit the greater number of crimes? Who has done the most burning and hanging and persecuting? The results would probably be too shocking to get published.”

Madalyn Murray works almost, but not entirely, alone. She has one employee at Other Americans, a strikingly pretty Negro girl named Marion Walker, age 28. I had heard that Miss Walker was a devout Baptist, but this turned out to be another of the many myths that have accumulated about Madalyn and her activities. “I’m not an atheist,” Mi. Walker told me, “but I gave up on the church a long time ago. I used to pray and pray and pray and all I ever got to show for it was dirty knees.”

I asked if working for a notorious atheist created any personal problems for her.

“Only occasionally,” she said. “There, one woman at the supermarket heckles me every time I go in there, but not much aside from her.”

How was Madalyn Murray as an employer? “Too nice, just too nice to be believed.”

Miss Walker spoke with a smoldering passion I couldn’t quite identify. “I can’t understand why all these Christians arc so cruel to her,” she went on hotly. “Throwing rocks through the windows, beating up her children, and then thinking they’re so superior. Mrs. Murray would never do anything cruel.

“Why that woman in the supermarket said to me when I was buying my Christmas ornaments, ‘Does your atheist boss believe in Santa Claus?’ You know what I did? I said to her right out, ‘Why, as far as I’m concerned Madalyn Murray is Santa Claus.’ You print that,” she told me. “You let all these people know that I never met a nicer woman in all my life.”

Later, with time to kill at the airport, I stopped for a haircut and asked the barber what he thought of Madalyn Murray. “A woman like that isn’t even a woman,” he said. “She’s no more than an animal. If this was still a Christian country we would have put her in jail long ago.”

On the plane leaving Baltimore, in a copy of the Baltimore Sun I had picked up, I found the following story:

MINISTER PRONOUNCES CURSE

ON BLACK MAGIC WORSHIPPERS

Bramber, England. Jan. 5 (AP)—Dressed in vestments and with his arms outstretched, the Rev. Ernest Streete stood before the altar of his 900-year-old church and pronounced a curse.

This was his answer to desecration of his church-yard, blamed by police on black magic worshippers.

“I pronounced a curse on those who touched God’s acre, and on their sacrilege and the terrible thoughts in their minds,” he said.

“May their days be of anguish and sorrow …”

Other black magic ceremonies have been held in the Southern Midlands, accompanied by desecration of graves and church ornaments.

Madalyn, I thought, you have a steep, uphill fight ahead of you.

![]()

The Most Hated Woman In America

by Robert Anton Wilson appeared in Fact, Volume 1, Issue 2 in March/April 1964.