He Makes a Career of Being Offensive

“In behalf of all the Jews in the world,” the telephone caller shrieked, “I am suing you for $50,000,000 damages.”

Paul Krassner, the editor of the nation’s most offensive magazine, The Realist, was not seriously bothered by the call. “Probably, I’ll never hear from him again,” he said, after hanging up. “Every issue pulls a few threats like that.”

The caller had been offended by such Realist pleasantries as suggesting Adolph Eichman’s theme song was “If I Knew You Were Coming I’d Have Baked a Kike” and labelling a Cadillac “Sedan de Kike.”

Krassner’s magazine has also offended Catholics by printing a picture of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child under the caption “Does She or Doesn’t She?” In this case, an irate Irishman wrote to say that he was going to crack open Krassner’s head with a hammer.

Religious and racial offensiveness is only part of The Realist’s general aggressiveness. Every four-letter-word in the language has popped up in its pages, Lyndon Johnson has been accused of perversion, American foreign policy has been ridiculed and denounced extensively, Lee Harvey Oswald has been proclaimed innocent of Kennedy’s assassination, and every steady reader has—at least once, and, more likely, very often—seen his own most cherished belief held up to scorn and mockery.

In spite of this free-wheeling policy—or, perhaps, because of it—The Realist, started on a shoe string as a completely one-man operation in 1959, has grown in circulation from 600 to 50,000 in only 6 years.

The editorial policy of The Realist is quite simple, according to Krassner: “The things I print have one thing in common: they couldn’t be printed anywhere else.” In following this editorial line, Krassner has been almost super-humanly impartial. The leader of the American Nazi Party, “Commander” George Lincoln Rockwell, has twice appeared in The Realist with a medley of his favorite charges against Jews, Negroes and liberals; William Worthy, a Negro reporter prosecuted by the American government for going to Cuba, several times appeared in The Realist, praising Castro and attacking the Pentagon; one Realist writer has defend the controversial Black Muslims, and another has damned them violently; atheist Madalyn Murray has contributed articles blasting all the Christian churches as superstitious folly; and the editor himself appears in every issue, mockingly tearing down the dogmatisms of reactionaries, conservatives, liberals and radicals—and also his readers, his contributors, and himself.

The Realist was the only magazine, outside of the extreme Right Wing, to print the evidence adduced to prove that John Kennedy had been married once before his marriage to Jackie, in violation of Catholic teachings; The Realist was the only magazine, outside the extreme Left Wing, to print the evidence adduced to prove that Lee Harvey Oswald was framed by the F.B.I.

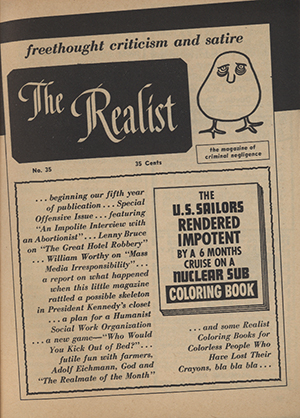

A typical Realist cover blatantly proclaims the magazine’s aggressive free-speech policy

Paul Krassner, the impresario of this carnival of heresy, is an unimpressive-looking cat, so youthful-seeming at 33 that visitors to his office at 318 E. 18th St., N.Y.C. frequently mistake him for the office boy and ask “Where’s the editor?” Not at all nonplussed by this, Paul once emphasized his youthful appearance by printing a picture of himself sitting on a fire hydrant, wearing his usual leather jacket and open shirt, looking for all the world like any neighbor-hood’s typical teenage punk. Obviously, Paul’s skeptical humor derives chiefly from his ability to accept himself unconditionally as he is, without taking himself at all seriously.

Married at 31, Paul Krassner is now separated from his wife, but betrays no bitterness over the failure of the marriage. Brooklyn-born Krassner, a graduate of CCNY, is sitting pretty days, being a ghost-writer for two nationally-famous comedians, and also pulling down a salary as Contributing Editor of a girlie magazine, as well as the earnings of The Realist. It was not always so: in the first year, when The Realist’s circulation was painfully crawling uphill from 600 to 1000, Paul lived with his parents and eked out an income to pay his printer’s bills by writing free-lance humor bits for TV and Mad magazine.

The Realist differs from other non-commercial magazines in not following one political “line,” and also in not taking itself seriously. Its masthead changes every issue, but is always self-mocking: “the magazine of lasting insignificance,” “the magazine of egghead junkies,” “the magazine of yellow journalism,” and, once, the stark slogan, “Pray for War.”

“I am against all censorship,” Krassner says tersely. Denying that the humor of The Realist is “tasteless” or “sick,” he says, “Humor is completely subjective. Tragedy and absurdity are not incompatible. It’s amazing that liberals will rush to my defense if the Catholics try to get me banned for printing so-called ‘obscene’ words, and then the same liberals will tell me I shouldn’t print ‘kike’ or ‘nigger.’ Jews and Negroes will have to learn to laugh at those words, to become free of them. We have to stop being afraid of free speech, even if it’s Lincoln Rockwell who is using it.” Paul Krassner himself is “Jewish,” according to the definition accepted by both Jews and anti-Semites: he is the son of Jewish parents. (Paul considers this definition absurd, and regards himself as a freethinker.)

An amusing Krassner anecdote concerns his friendship with a teenage Nazi, who lived in his neighborhood. When this boy said that liberals were just as intolerant as Nazis and tried to suppress Nazi opinions, Paul replied, “You write an article on why you are a Nazi and I’ll print it in The Realist.” The boy wrote the article, and Paul did print it, to the dismay of many readers. Later, the boy invited Paul to accompany him to a showing at Cinema 16—an avant-garde film society—of the notorious Nazi propaganda film, “The Eternal Jew.” One of the highlights of the film was a graphic depiction of the animal-slaughter methods used by religiously orthodox Jews in accordance with Bible teachings. “Did you see that?” the boy cried. “Doesn’t that prove Jews are cruel?”

“Well,” Paul said, “if Rockwell takes over this country, you’d push me in an oven wouldn’t you? Isn’t that cruel?”

“No,” the boy said thought-fully. “I’ve been thinking that over, and you’re different. Jews like you I’d just sterilize.”

“Gee,” Paul replied soberly, “It’s nice to know somebody cares …”

As this article goes to press, the latest issue of The Realist has just appeared on the news-stands, as raunchy and iconoclastic as ever. The cover has a picture of Lyndon Johnson upside-down, together with an article by Norman Mailer suggesting that everybody who disapproves of the war in Viet Nam should hang pictures of Johnson upside down as a form of protest. Inside is a double-page spread of “Soft-Core Pornography: Phallic Symbolism Department,” showing Joe Dimaggio kissing a bat, Lyndon eating a hot-dog, a cigar advertisement, etc. In another feature, a Negro reporter in Santo Domingo attacks the American troops and defends the rebels. A religious tract against profanity is reprinted under the jeering title, “Department of Unintentional Satire.” A cartoon shows one ancient Jew cheerfully telling another, “Hey, Onan, you made the Bible!” Another article attacks the Progressive Labor Movement as totalitarian. A short piece reveals that a souvenier collector has purchased, for $10,000, the rifle used to assassinate Kennedy, and suggests that we also auction off the axe used by Lizzie Borden to kill her parents, the bottle of pills used for suicide by Marilyn Monroe, and the four nails employed in crucifying Christ.

Many prominent writers have sent articles to The Realist which they knew they could not get printed anywhere rise. Among them have been Terry Southern (author of Dr. Strangelove and Candy), sexologist Albert Ellis, Mailer, Lenny Bruce, Theodore Sturgeon, Jules Feifer, Joseph Heller (author of Catch-22), and Lawrence Barth. It is altogether possible that the writings of these men which were unprintable except in The Realist will be their best-remembered pieces, one hundred years from now. “I’m a happy man,” Paul Krassner tells interviewers. “I’m doing exactly what I want to do, and making a living from it.” Very few other people in America could make that statement.

He Makes a Career of Being Offensive

by Robert Anton Wilson appeared in PHOTO, Volume 2, Issue 9 in December 1965.