Death Universe: A Review of Mondo Cane

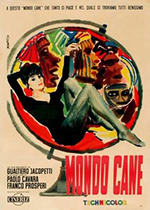

Mondo Cane (1962)

written and directed by Paolo Cavara

I don’t want no more of your rotten old Death universe …

— William S. Burroughs, The Soft Machine

A man’s arm appears on the screen, dragging something on a leash. The camera pans downward and we see a dog struggling desperately. On the soundtrack we hear the barking of other dogs — hundreds, thousands of dogs, howling in rage and anger. A gate opens and the dog that we have been watching is brutally picked up and thrown into a dog-pound. On the screen appears the title, Mondo Cane (“A Dog’s World.”)

Not since the gruesome opening shot of Dali’s Andalusian Dog has a movie so frankly and sensationally yanked hold of the audience’s emotions. Mondo Cane, is indeed, much indebted to Dali’s earlier exploration of cinematic morbidity; under the facade of “naturalism”, this new Italian film is as surrealistic as Dali’s, and, like Dali’s, is primarily a cry of outrage against the fabric of reality itself.

I am aware that the critic in the Saturday Review has described Mondo Cane as being merely “tasteless and sensational”. I am also aware that Leo Tolstoy made the same idiotic remark about King Lear. Mondo Cane, in my opinion, is as serious and genuine a work of art as anything I have ever seen on the cinema screen.

With great and Nietzschean contempt for his audience, the director has made this movie into an imitation of the popular travelogues of the past thirty years, complete even to the moronic narration that such epics usually have, skillfully “written down” to the 12-year-old level that the mass audience is supposed to possess. The irony is poker-faced throughout; only once or twice does it become broad enough to arouse widespread laughter in the audience. The monotonous voice drones on, finding everything on the screen either quaint or edifying or just downright “cute”; but what we are seeing behind this voice is a carefully edited catalog of unmitigated horrors. It is like touring through Dante’s Hell with the cheerful voice of Arthur Godfrey chirping in your ears. It is, indeed, a perfect symbol of the semantic jungle of the modern world, as typified in America by the Huntley-Brinkley type of newscaster with his brisk detachment from the fallout figures and other terrors which he is chronicling. Carried to an extreme, this bright-eyed refusal to face real horrors leads to schizophrenia. The American mass-communications industry is a monument to that kind of schizophrenia, but Mondo Cane, an Italian film, reminds us that the plague is now nearly universal.

The editing of this film is of genius caliber. After the opening shot of the condemned dog we do not proceed immediately into other horrors, but stop off first at a rather “light” and amusing vignette in the town where Rudolph Valentino was born. Several men of the town, conscious of the cameras, are deliberately imitating Valentino’s seductive half-feminine half-masculine pout: you can see in each of them the dream that the movie crew will “discover” him and make him overnight as rich and famous as Valentino. The director has saved from the antics of this group only the carryings-on of the ugliest and most hopeless of these men. Each of them arouses laughs from the audience and is, in fact, a clown; each imagines that he is a handsome and irresistable Apollo. This spectacle of vanity and self-deception is amusing enough, but it is apt to become increasingly depressing if you think about it too long. It is the perfect introduction to the horrors that we will witness as the movie proceeds. A few moments later we are witnessing the ritual murder of some pigs by an African tribe, one of the bloodiest and most gruesome spectacles ever shown on a movie screen. The audience is forced to make a mental connection: is not this brutality caused by the same vanity as the clowning of the soidisant Valentinos? Is not man’s idea that he is so far superior to the pigs that he may murder them with impunity a great and terrible vanity indeed? Is there not the same lack of perspective in both groups? A bit later we see the barbaric feeding of the French geese specially bred for pate de foi gras: pipes are rammed down their throats and the food is pushed down by sheer brute force. The idiot voice of the narrator cheerfully comments that in the old days the geese’s feet used to be nailed to the floor, but we are more civilized now. Instead, the poor birds are locked in hideous cages too small to allow them to move.

Most of the sequences revolve around this same theme of human vanity and man’s barbaric cruelty to the other animals on earth. One sequence suddenly reverses the image and we see the armless and legless people of a Pacific island horribly plagued by sharks. This is, actually, the most important sequence in the film, because it serves to remind us that man, alone, did not invent evil. Evil is in the very fabric of the universe; this is a “dog’s world”, indeed. Such a thought is so uncomfortable that most people never face up to it for a moment in their lives. The last sequence shows how one typical group goes about evading this insight: a tribe in New Guinea who worship cargo planes. “Since the planes are in the sky, they are more than human; someday they will land and bring happiness to all of us.” But the planes, of course, never land; they are just passing over on their way from China to Australia. The movie ends with a group of cargo-cultists sitting around a bonfire at night, watching the sky, hoping for the supernatural deliverance that will never come. This cult is so absurd, and so pathetic, that it serves as a symbol of all religion and of mankind’s eternal desire to escape knowing what a “dog’s world” this really is.

Is there no ray of hope anywhere in Mondo Cane? None, just as there is none in Euripedes‘ Bacchanae, in King Lear, or in that other great epic of sharkish brutalities, Moby-Dick. Mondo Cane is one of that handful of art-works which dares to present a totally pessimistic philosophy. The agony and sincerity of such a vision is too brave a thing for me to have the affrontery to patronize it by claiming to know better than these artists. The strongest sequence in Mondo Cane is an island gone insane: standing too close to Bikini, this island has got an over-heavy dose of atomic radiation. Here sit birds hopelessly trying to hatch eggs rendered sterile by fallout. More terrible, in a different way, are the lunatic fish who have taken to living in trees. Worst of all are the turtles who have lost their basic instinct; after laying their eggs, instead of returning to the sea, they head inland where they soon die of thirst, making futile swimming motions in the water that isn’t there. This island of horror is a glorious vision indeed of what “human ingenuity” can do to the world, and it is a foretaste of what our whole planet may be like in a few years if nuclear research continues. Anybody who wants to complain that the director of Mondo Cane is a cheap cynic, or that art must always be affirmative, would be well advised to try to change the real world first. Art, after all, is only symbolic. If the symbols disturb you, friend, take a long, hard look at the reality which inspired them, and change that. The artist is only a recording instrument:

I am the Defense Early Warning Radar System

I see nothing but bombs

wrote the great American poet, Allen Ginsberg. If you want modern artists to see something a bit more cheerful, make a world a bit more cheerful for them to see.

![]()

Death Universe: A Review of Mondo Cane

by Robert Anton Wilson appeared in American Atheist, Volume 6, Issue 3 in March 1964. Many thanks to Jesse Walker for finding and sharing it.