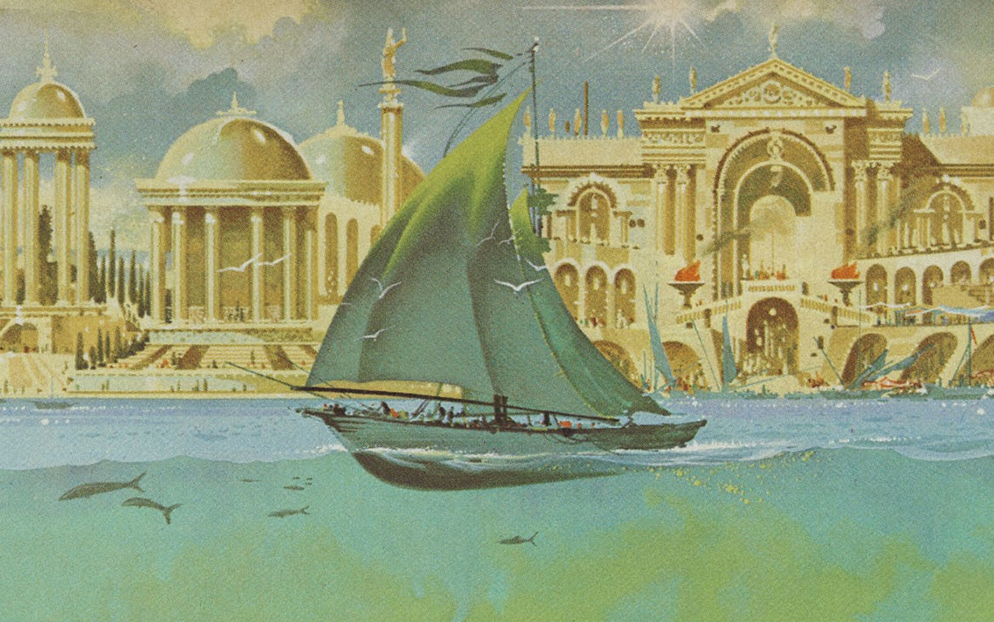

Atlantis

20,000 theories under the sea

What it is or isn’t

Originally Atlantis was the name of an alleged lost continent that sank into the Atlantic Ocean around 9000 B.C. This version, which is the origin of all Atlantis lore and theories, cannot possibly be true, but that doesn’t really matter, because if Atlantis isn’t an underwater continent, maybe it’s an island or even a lost city on dry land. Atlantis has been identified by various seekers in Spain, Sweden, North Africa, Russia, Mexico, Sri Lanka and California, among other places. Now the eminent Dr. Jacques-Yves Cousteau is off on a year-long, $2,000,000 search for Atlantis in the Aegean Sea.

Who started it all?

Platon Aristokles (better known as Plato), that’s who. Actually Plato didn’t claim to have any personal knowledge of Atlantis: He merely reported hearing about it from his uncle Critias, a Greek politician even more unsavory than Spiro Agnew. And Critias, in turn, heard it from his grandfather, another Critias, who heard it from Solon, another politician, who claimed he heard it from an anonymous Egyptian priest. Worse yet, this yarn claims that Atlantis and Athens fought a war in 9000 B.C., and we now know that Athens didn’t even exist until around 800 B.C.; many historians regard the whole Atlantis tale as Plato’s contribution to patriotic mythology, since the Athenians were the heroes of the story as he told it, and he was an Athenian.

Did the ancients believe Plato?

Evidently not; there are hardly any references to this yarn in surviving manuscripts. Aristotle, Plato’s pupil, did mention it, but dismissed it as a fable. Pliny the Younger also mentioned it, with the noncommital phrase, “as far as we can believe Plato.” The first one who did take Atlantis seriously appears to have been a nutty Christian theologian named Kosmas Indikopleustes, who added some details of his own to bring the tale into harmony with Holy Writ. According to Indikopleustes, Atlantis was the Garden of Eden and the ten kings of Atlantis (in Plato) were the ten generations between Adam and Noah (in Genesis). Nobody but fundamentalists and flat-earthers takes this seriously nowadays.

Could there be a lost continent in the Atlantic?

Absolutely not—unless everything we know about geology and oceanography turns out to be wrong. Continents may drift apart, and probably do, but they don’t sink. Coast lines and sometimes islands sink, so we can imagine a continent sinking, but it doesn’t really happen. (For an analogy: We have seen Olympic weight lifters raise several hundred pounds over their heads, so we can imagine Superman raising a skyscraper on edge; but in the physical universe, the skyscraper would not rise: It would fall on him.) Oceaaographers certainly do not know every square inch of the Atlantic bottom, but they know enough of it to agree that there is no continent lying down there.

Could Alantis be smaller than a continent?

If Plato got his dimensions wrong, yes. And if he got his directions wrong, Atlantis could be anywhere. It is on the assumption that Plato was in fact wrong about dimensions and directions that the search for Atlantis continues.

Why look for Atlantis?

Archaeology is a notoriously incomplete science, and any new expedition might make a major discovery. Archaeology is incomplete because it does not produce weapons or products that can be mass-manufactured, so governments and big foundations are more inclined to donate huge sums to more practical sciences such as physics, which gave us atomic bombs and TV sets. Most of the places where important archaeological discoveries might be made (e.g., in Egypt and Mexico) still have not been excavated systematically, for lack of money. As Dr. Cousteau said, when leaving on his expedition to find Atlantis, “Of course we will be successful. Even if we don’t find what we’re looking for, the search is always worth the effort.”

Could Atlantis be a generic name?

We know virtually nothing about the origins of civilization, or language, or religion. Atlantis has become a generic name for one of the four most popular theories about these enigmas of man’s becoming and other mysteries of the prehistoric ages. In order of scientific respectability, these four theories are:

- The parallel-development theory. The human mind is much the same everywhere, this school argues, and the problems of survival on this planet are also much the same, so the logical deduction is that every major civilization appeared independently. The Mayans and Egyptians both built pyramids, in this theory, because it was natural for man to invent the architectural-geometrical ideas that led to building pyramids.

- The diffusionism theory. The ideas found in all the great civilizations, this theory contends, were invented at one place at one time, and spread from there; e.g., either the Mayans copied Egyptian pyramids, or the Egyptians copied Mayan pyramids. The intrepid Professor Thor Heyerdahl is a hard-core diffusionist theorist, and his daring voyages across the Pacific and Atlantic via

primitive boats or rafts were attempts to prove that such diffusion could occur long before advanced technology appeared on earth. - The lost-civilization, or Atlantis, theory. This is the ultradiffusionist position that claims that the one place where everything was invented is a now-forgotten civilization that became the basis for Plato’s admittedly half-fictional Atlantis. The Mayan and Egyptian pyramids were copied from those in the generic “Atlantis,” wherever that was.

- The extraterrestrial theory. Language, civilization and pyramids were all given to us by ancient astronauts from an advanced civilization in outer space.

Almost all of the evidence used to support any one of these theories will reappear, somewhat reinterpreted, in the presentation of the other theories. The first two (parallel-development and diffusionism) have usually been argued by scholarly persons with careful documentation, and the latter two (Atlantis and the extraterrestrial) often by flamboyant writers with careless documentation.

Prominent Atlantologists

In 1680, a Swedish scholar named Olof Rudbeck proved that Atlantis was in ancient Sweden and that the capital of Atlantis was in his own home town, Uppsala. In 1685, Georg Kasper Kirchmaier proved that Atlantis was really in South Africa.

At the end of the 18th Century, Jean-Sylvain Bailly proved that Atlantis was in the Arctic Circle, near Spitsbergen. About that same time, Delisle de Sales proved that it was in Central Asia. At the beginning of this century, the German anthropologist Leo Frobenius (who also got Picasso interested in African art and thus mutated modern painting) put Atlantis back in Africa, but, contrary to Kirchmaier, insisted that it was in the northern part of that continent, around Sudan.

In 1952, rocket pioneer Willy Ley and sci-fi writer L. Sprague de Camp proved once and for all that Atlantis was in what is now Cadiz, Spain.

In the late Fifties, a Greek seismologist, Dr. Angelos Galanopoulos, again proved once and for all, beyond all doubt, that Atlantis was really the sunken island of Thera, in the Aegean Sea. An English oceanographer, James W. Mavor, found a lot of evidence in the late Sixties, while diving into sunken Thera, that Galanopoulos was right. Dr. Cousteau is currently diving there to clinch the case for the Galanopoulos theory.

Some more far-out Atlantologists

Augustus Le Plongeon, the archaeologist who first excavated the Mayan ruins in Central America, was frustrated by the fact that there was no way to translate the Mayan hieroglyphics. He determined to stare at them long enough for the meanings to appear to him by intuition. Although this procedure is not generally considered scientific, Le Plongeon got results that satisfied himself. He deciphered that Atlantis was, by God, in the Atlantic Ocean after all, that it was called Moo, and that Egyptian civilization was founded by a royal lady of Moo, herself called Queen Moo, who became the cow-headed goddess Isis in Egyptian art. Virtually no other scholar has accepted this translation.

Dr. Paul Schliemann, grandson of the famous Heinrich Schliemann who excavated the ruins of Troy, claimed to have outdone grandpa by finding the ruins of Atlantis. Later, it turned out that his evidence was not exactly found but more precisely manufactured by himself, and that’s against the rules in science.

Colonel James Churchward proved that Mu (his corrected spelling of Le Plongeon’s Móo) was really in the Pacific, not the Atlantic. Madame H. P. Blavatsky, of the Theosophical Society, did even better. She found a third lost continent, Lemuria, in the Indian Ocean and proved that it had been inhabited by bisexual ape men.

Karl Georg Zschaetzsch proved that Atlantis was the ancient homeland of the Aryan race, who were originally all vegetarians. He added that it was destroyed because the Atlanteans became alcoholics. This theory was a favorite with Hitler because of its racist slant and its anti-booze theme. But Adolf was more interested in a fourth lost continent, Thule, allegedly located in the North Atlantic. (He heard about Thule from Hörbiger, the nutty engineer who also convinced him that the sun was made out of ice.)

W. Scott-Elliot—a major influence on the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft and on the enigmatic writings of Richard Shaver (see following) proved that the Atlanteans had battleships, telepathy and priestesses in transparent silken gowns. Lovecraft lifted a lot of Scott-Elliot’s rhetoric, to make his horror stories more convincing, and added R’Lyeh, a lost island in the Pacific ruled by a monstrous being named Cthulhu.

Shaver, borrowing from both Lovecraft and Scott-Elliot (especially those priestesses in transparent nighties), published his revelations in the pulp sci-fi magazines of the early Fifties. They were written like fiction of the most juvenile sort, with lots of fast action and short sentences, but Shaver and his cohorts always claimed that the stories were true. The thesis was that Atlantis and Lemuria both existed; also, that their citizens invented atomic bombs and flying saucers and that the survivors are now living inside the earth, which is, of course hollow. They come out in their flying saucers through a hole at the North Pole.

Shaver also led a crusade against the deros — deranged robots — which were designed by the Atlanteans and then like Frankenstein’s monster turned mean. Shaver, himself positively saw them in caverns under New York City.

He says.

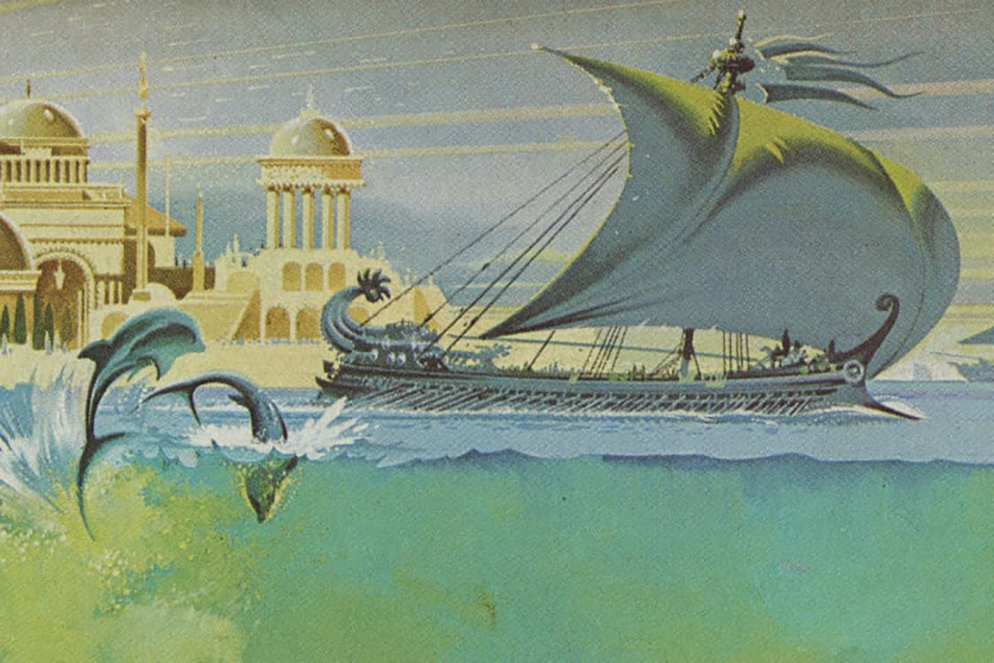

Atlantis in literature

In addition to Shaver and Lovecraft, many other writers have explored the Eldritch mystery of the sunken continent. Robert E. Howerd creator of the famous blood-and-thunder Conan the Barbarian series, also wrote a group of tales about King Kull of Atlantis — a superhero of the Conan (or Tarzan) variety whose mighty muscles were often pitted against wicked antediluvian wizards and serpentmen. Namor, the Submariner of Marvel Comics, is prince of Atlantis and seems to be of the same genetic superstock as Conan and Kull. Aleister Crowley, the most controversial of all modern occultists, wrote his own novel about Atlantis, in which the lost continent came to a bad end, because it abandoned the law of Do What Thou Wilt (a phrase from Rabelais that Crowley made the center of his own teaching) and became embroiled in morality and repression. Even Taylor Caldell, queen of the women’s novelists, has done her own Atlantis saga (The Romance of Atlantis), and Donovan has written a song about it. Finally, as if the poor lost continent hasn’t suffered enough, an obscene, subversive, blasphemous and pornographic three-volme sci-fi saga, Illuminatus!, seriously claims that the world has been governed behind the scenes by a circle of Atlantean mad scientists for the past 30,000 years.

The Cayce prophecy

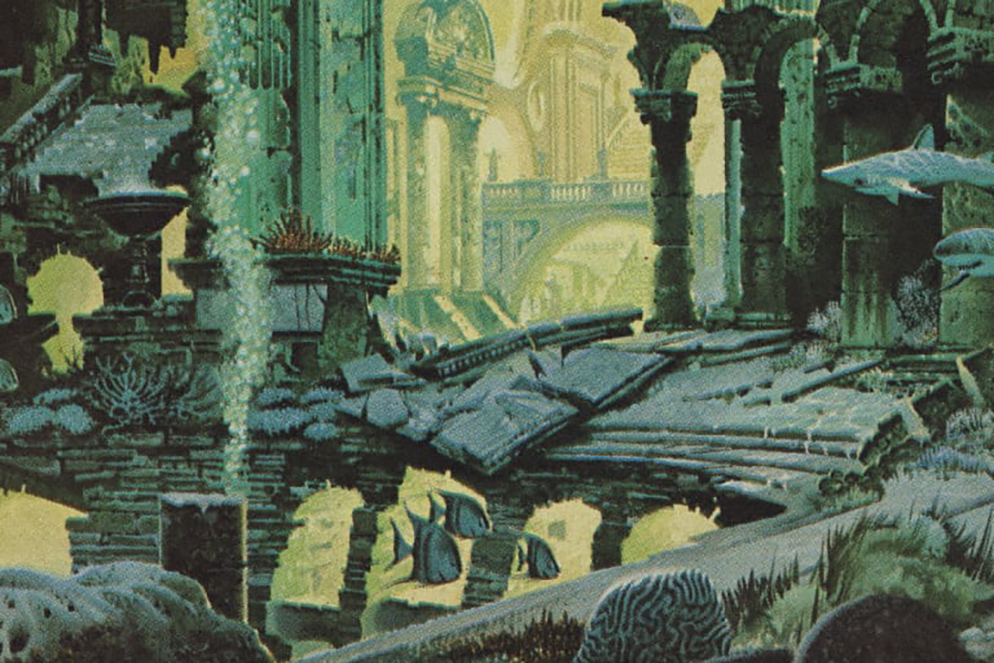

Edgar Cayce, an American with remarkable talents for psychic healing and (sometimes) for prophecy, predicted. in 1940 that part of Atlantis would rise again in 1968. Parts of submerged buildings were found near the surface of the Atlantic, near Bimini in the Bahamas, in 1968. This has been a great comfort to all those seeking Atlantis in the Atlantic. Those who are seeking Atlantis elsewhere say the buildings appeared to be part of a Mayan settlement.

Etymology

Ignatius Donnelly, one of the most scholarly, if erratic, Atlantologists, was fascinated by the name that the Aztecs gave to their legendary land of origin, Aztlán. Just say Aztlán-Atlantis three times aloud and you will see how suggestive this is.

Others have been equally struck by the name Attala, the alleged homeland of the Berbers of North Africa. Attala-Atlantis is rather persuasive, too, if you say it a few times.

Charles Berlitz, grandson of the Berlitz who founded the language schools, claims a common Atlantean origin for Aztlán, Attala, Atlas (the Greek god but also a king of Atlantis in Plato’s story); Avalon (the Celtic paradise), Tlapallan (home of Quetzalcoatl, in Mexican myth) and even the name of the Antilles Islands, which might be part of sunken Atlantis, he reckons.

But Mark Twain claims to have known a scholar who derived the American Middletown from the Hebrew Moses. It’s easy. You just drop the -oses and add the -iddletown.

The Bermuda Triangle

The allegedly Atlantean ruins found under the Atlantic near Bimini are in the enigmatic Bermuda Triangle where so many ships and airplanes have disappeared mysteriously. Berlitz and others have wondered if Atlantean machinery, still working but based on scientific laws unknown to us, might be slurping these craft down to the bottom or outward to the fifth dimension or something like that, a sci-fi concept that is also found in Lovecraft and Shaver.

The sun-god problem

Sun gods, or divine beings with halos around their heads, are found in religious art almost everywhere. Atlantologists claim that these beings were all derived from the protoprimus sun god of Atlantis, Ra – origin, they say, of the Egyptian Ra and even, according to some, of the Hindu Ram. Parallelists say that the sun god is just a natural primitive concept, based on mankind’s need for the sun to make his crops grow. Jungian psychologists, who are genetic parallelists, say further that the sun god is an “archetype of the collective unconscious.” The Von Daniken school, of course, says that the sun gods are ancient astronauts with their space helmets on.

Thera

Dr. Galanopoulos‘ claim that the real Atlantis was the sunken island of Thera in the Aegean Sea is now the most popular theory among scientific Atlantologists. Unfortunately the capital city of Thera is 11 miles wide and the capital of Atlantis, in Plato, is 110 miles wide. An error of 99 miles, however, is nothing to Atlantologists. Plato’s dimensions are all wrong, anyway, they point out, and Galanopoulos even explains why Plato was off by a factor of ten. The Greeks, he says, confused the Cretan symbol for 1000 with the one for 10,000.

Quite simple, really. You just drop the -oses and add the -iddletown.

Atlantis: 20,000 theories under the sea

by Robert Anton Wilson, with illustrations by Paul Alexander appeared in OUI in January 1977.