The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Now that I’m six, I’m clever as clever,

So I think I’ll be six for ever and ever.

— A.A. Milne

A sports car races down a highway. The driver’s face is grim and determined. He parks before a government building, strides angrily down a long hall, slams something onto a desk. Thunder crashes ominously as he paces back and forth, obviously making a denunciatory speech to an unseen official. A computer-operated system moves his photo into a file marked “Resigned.” He returns to his home and begins packing for a trip; but he is destined for a far weirder trip than he imagines. Two thin, corpse-like men in incongruous high silk hats approach his doorway; a gas seeps through his keyhole; he collapses unconscious.

He awakens in a village that seems to be the archetype of old English rural charm. Everywhere there are people with high silk hats; equally ubiquitous is the image of Edwardian holiday amusements: the “penny-farthing” bicycle (the model with a giant front wheel and a midget back wheel). But behind this idyllic facade is a computer complex and a group of highly professional technicians using all the latest scientific techniques of mind-programming and brainwashing. The same resonantly ambiguous dialogue is repeated, after the above images, at the beginning of each episode:

“Where am I?” the hero demands.

“In the Village.”

“Which side are you on?”

“That would be telling.”

“What do you want?”

“Information.”

“You won’t get it!”

“By hook or by crook, we will.”

“Who are you?”

“Number Two.”

“Who is Number One?”

“You are Number Six.”

“I am not a number – I am a free man!”

The answer is mocking laughter.

I have been describing the opening scenes of the most remarkable series ever to hit TV: The Prisoner.

It was originally shown in this country in 1968, repeated in 1969, and is now back again (on public TV this time). In the San Francisco Bay Area, the revival has been so popular that The Prisoner is already scheduled for a fourth showing, this summer.

This is a rather remarkable success story, since virtually all the TV critics reacted to The Prisoner, in 1968, by praising it with faint damns and predicting that it would be a commercial failure because it was “over the heads” of the alleged morons who are supposed to be the only ones who ever look at The Tube.

Even more interesting, 10 years after its first appearance here (eleven years after its premiere in England), The Prisoner has even become a cult. There are actually Prisoner T-shirts, saying “I am not a number: I am a free man,” for sale in head-shops.

The reason for this unique success of a show that is admittedly arty, ambiguous and emotionally disturbing is that the world of Number Six is our world; the mysteries and anxieties he confronts are those that we all confront these days. And the ringing defiance of his slogan, “I am not a number” (expanded, in the first episode, to “I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed or numbered!”) is symptomatic of both the growing libertarianism and the growing paranoia of vast masses of people who have become aware that government is not the benign institution we are told it is in high school civics classes and official Liberal philosophy.

Dig: the most disturbing, and most violent, expression of Number Six’s lonely struggle to preserve his sanity and regain his identity occurs in an episode in which he finds himself in “Harmony,” a town in the American West sometime in the last century. (Time-travel? Hallucination? The audience is given no clues: Number Six is simply there.) A group of hooligans are beating him up – the most explicit and brutal beating in the whole series. Onto this violent image comes the title of the episode: “Living in Harmony.”

(“What is true peace?” R.H. Blythe once asked a Zen Master. “Two drunks fighting in an alley,” was the answer. Do I digress?)

Harmony turns out to be much like the Village. A judge continually seeks to pry out of Number Six why he resigned from his last job (as sheriff in a nearby town), just as the various brainwashers in The Village try to learn why Number Six quit whatever branch of government he was quitting at the beginning of the series. A psychopathic killer stalks about terrorizing Harmony, and wearing, not a Western hat like the other characters, but the high silk hat of the Village. What the hell is going on

here?

Every effort is made to persuade/coerce Number Six into becoming sheriff in Harmony. When he finally accepts, he (by the logic of another world) refuses to wear guns. This non-violence does not work in Harmony, of course, and eventually Number Six is maneuvered to wear his guns and use them (in self-defense, of course), seemingly killing a half dozen bandits. Everything abruptly turns into two-dimensional cardboard cutouts and Number Six is back in The Village again. Has he really killed anyone?

Well, it turns out that he hasn’t, but the brainwashers, using LSD and hypnosis almost had him convinced that he had killed several people. Ambiguity? Symbolism? Allegory? You would be naive to take “Living in Harmony” only on that level. While The Prisoner was being produced, we now know, similar experiments were being conducted by (among others) the U.S. Army. Operating Mind Control by W.H. Browart (Dell, 1978) gives several cases of persons who, like Number Six, were sent into fantasies, via drugs and/or hypnosis, in which they attempted to kill people who seemed to them to be somebody else. For instance, one private was induced to attempt to strangle his own superior officer, under the hallucinatory impression he was in hand-to-hand combat with an enemy soldier. In Soviet experiments also described by Browart people were sent into hypnoidal fantasies in which they committed “crimes” for which they afterwards felt guilty, even though the acts never happened in public “reality” but only in the “reality” of their own programmed impressions and memories.

The irony behind all other ironies of The Prisoner’s Dilemma is that nothing in the whole series is merely arty, or ambiguous, or obscure, as nearly all the TV critics think it is. Everything is a perfectly accurate documentary presentation of modern brainwashing techniques.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

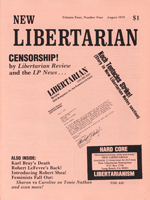

appeared in Robert Anton Wilson’s column “Illuminating Discords” in New Libertarian, Volume 4, Issue 4 in August 1978.